“Boy in the bubble” David Vetter passed his life in a sterile enclosure breathing purified air and touched only with plastic gloves. While his parents and doctors attempted to make his life as normal as possible, they lived in fear of the tiniest exposure to common impurities and infections. He died aged 12 in 1984, after a bone marrow transplant given in the hope of building up his immune system.

Most of us can be thankful that we don’t live with a severe combined immunodeficiency like David’s, a condition so rare that his life inspired a John Travolta movie.

Peggy Noonan later brought the image into political parlance when she spoke about Ronald Reagan’s isolation in the White House…

“Do you ever feel like the boy in the bubble?” Ms. Noonan asked.

“Who was that?” Mr. Reagan replied.

“The boy who had no immune system,” said his speech writer, “so he had to live in a plastic bubble where he could see everyone and they could see him, but there was something between him and the people, the plastic. He couldn’t touch them.”

“Well, no,” Mr. Reagan said.

Then he thought it over: “No, but there are times when you stand upstairs and look out at Pennsylvania Avenue and see the people there walking by. And if I wanted to run out and get a newspaper or magazine, or just to walk down to the park and back . . . you miss that, of course.”

— William Safire, ‘ON LANGUAGE; The Man in the Big White Jail’

In medicine and politics, we pity people with this condition. Why then do we so often go to work as if in a bubble ourselves, cut off from human contact with users and the people who deliver everyday service?

- Days and weeks of work are put into consultation documents, leaving only a narrow window for citizen feedback on a limited range of pre-defined questions.

- Executives employ management consultancies to spend months putting together process models and business cases unchecked by exposure to the realities up on the shop floor.

- Some organisations become so afraid of their customers that unmediated face-to-face engagement with the public requires a risk assessment, as if it were primarily a health and safety issue.

Let’s call this mode of operation “bubble work”. Like failure demand it’s a major source of waste and poor service in our society.

Bubble work is a waste of our own time. We think we’re being clever, applying our past experience, creating a good framework for activity. But until our guesses meet the real world, that’s all they are, guesses – when we can so easily go and find out for sure.

Bubble work is a waste of other people’s time. Every time we create a “straw man” or a “starter for 10” we shuffle the burden of understanding onto other people, who are then obliged to unpick our web of assumptions before they can share their own realities.

Bubble work depresses quality. The more we elaborate and decompose our untested reckons, the more they crowd out the new ideas and innovation that we would discover from interacting with users and frontline workers. As designer Mike Laurie says, untested ideas are excess inventory.

Bubble work comes back to bite us. It can only ever defer the moment at which our cherished ideas meet the messy complexity of the real world. But the encounter is all the more painful when it comes. Not only are we more invested in the bubble work, we have less time to deal with the consequences.

I know all these things because over the years, I have lost months of valuable project time to bubble work. I have made complex multi-year business cases built on the tottering edifices of “expert” assumptions. I once worked on a project so super-sensitive that we were forbidden by lawyers from researching it with potential customers. Neither of those things worked out well.

We see this damaging pattern equally in the private and public sectors, and while it’s often a big organisation malaise, so-called “stealth start-ups” can easily fall victim to the same fallacies. The world is awash with bubble work, and it has to stop.

Here’s how…

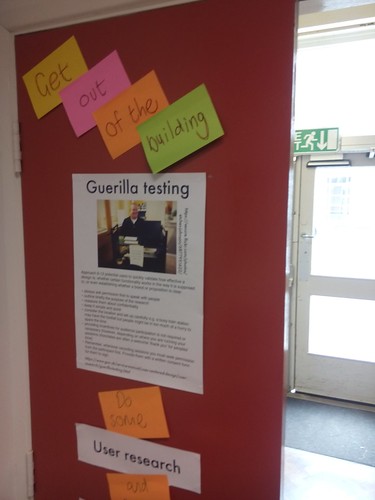

Every time we’re tasked with a new mission, let’s start the clock. Let’s see how fast we can get to users. At Leeds GovJam every team achieved this within 24 hours. They surprised themselves by drawing up questions and making prototypes to get meaningful insights from people on the street – and came back with their ideas re-shaped by potential users.

While working even briefly in the bubble, let’s be single-minded about bursting it. We should stamp all our assumptions as such, and always be thinking of ways to test them with actual users. Every statement we write at this point is a hypothesis to be accompanied by the questions we’ll ask to check whether it’s true.

When we spot others doing bubble work, we must call them out. Let’s ask how they know what they know, when they last spoke to users, and what took them by surprise. If their answers are unconvincing, we should not be enablers. We should spend not a moment more of our days engaged with their assumptions.

Doing these things may feel like a risk. It may feel like we’re slowing things down, but the payoff later will be consistency of pace. It may feel like we’re undervaluing our experience, but the reward comes when we keep on learning and deepening our expertise in an ever-changing world.

We are not David Vetter; we are not Ronald Reagan. Getting out of the building has never been easier. It’s time for zero tolerance of bubble work.

One thought on “Real work only begins when we break out of our bubble”