“In Elizabethan amphitheatres, like the 1599 Globe Theatre, performances took place in ‘shared light’. Under such conditions, actors and audiences would be able to see each other… This attention to a key original playing condition of Shakespeare’s theatre enables the actors to play ‘with’ rather than ‘to’ or ‘at’ audiences. Actors therefore develop their ability to give and take focus using voice, gesture and movement.” — Emma Rice to Step Down From London’s Shakespeare’s Globe, Playbill, Oct 25, 2016

Early, too early, one morning I blunder into a railway station Starbucks for a coffee and croissant to take onto the train. I’m the only customer. I place my order and shuffle along to the end of the counter where the barista will hand down my drink.

What happens next in the customer experience is critically important. We know that Starbucks knows this too, because of a leaked 2007 memo from chairman Howard Schultz, in which he bemoaned the commoditisation of his brand:

“For example, when we went to automatic espresso machines, we solved a major problem in terms of speed of service and efficiency. At the same time, we overlooked the fact that we would remove much of the romance and theatre that was in play with the use of the La Marzocca machines. This specific decision became even more damaging when the height of the machines, which are now in thousands of stores, blocked the visual sight line the customer previously had to watch the drink being made, and for the intimate experience with the barista.”

As I said, it was early, much too early for an intimate experience with a barista. And in any case, the barista was still learning the ropes. I guess first thing on a shift, when there’s one customer and no queue, is a great time for some coaching from the supervisor. This is what I heard him say:

“You have 23 seconds for the milk… Oh, and relax. You can’t concentrate when you’re stressed.”

23 seconds! That’s what removed the romance from my coffee.

“You must either make a tool of the creature, or a man of him. You cannot make both. Men were not intended to work with the accuracy of tools, to be precise and perfect in all their actions. If you will have that precision out of them, and make their fingers measure degrees like cog-wheels, and their arms strike curves like compasses, you must unhumanise them.” — John Ruskin, The Nature of Gothic

Some things in this carefully commodified service experience were never meant to be seen by the customer. When they do burst into view, it feels wrong, uncanny.

In this post I want to explore the reasons for that uncanniness, and how we might play with it to develop new service opportunities. Is it really so obvious what should and should not be visible to the user? What’s the impact on users when a component slips out of sight? And how might we make service better by keeping more things, more visible for longer?

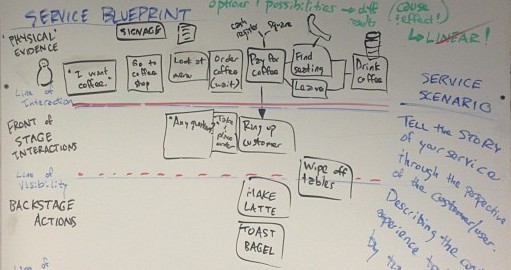

The line of visibility

The line of visibility is a well-known concept in the fields of customer experience management and service design. To use, like Howard Schultz, a theatrical metaphor, it divides the service blueprint into front-stage activities seen by the customer, and back-stage ones unseen by the customer but nonetheless essential to the delivery of the service.

In the coffee shop:

- Front-stage: the theatre and romance of taking the order, writing the customer’s name on a cup, grinding the beans, making the coffee, presenting the coffee to the customer

- Back-stage: the operational efficiency of managing rosters, training staff, timing operations, replenishing stock, and so on.

At first glance, the allocation of activities to front or back-stage appears uncontroversial. In reality, it is much murkier, and deserves more critical attention:

- A restaurant might make a show of fresh food preparation with an open kitchen on full view to the diners, but still have a room behind the scenes for the freezers and dishwashers.

- Recently, after returning a hire car, I was given a lift by a new member of staff. The conversation we had about the rental company’s graduate scheme made me warm to the company and more likely to return.

- Much has been written about the 8 simple words on the underside of the machine on which I’m typing this now: ‘Designed by Apple in California. Assembled in China‘.

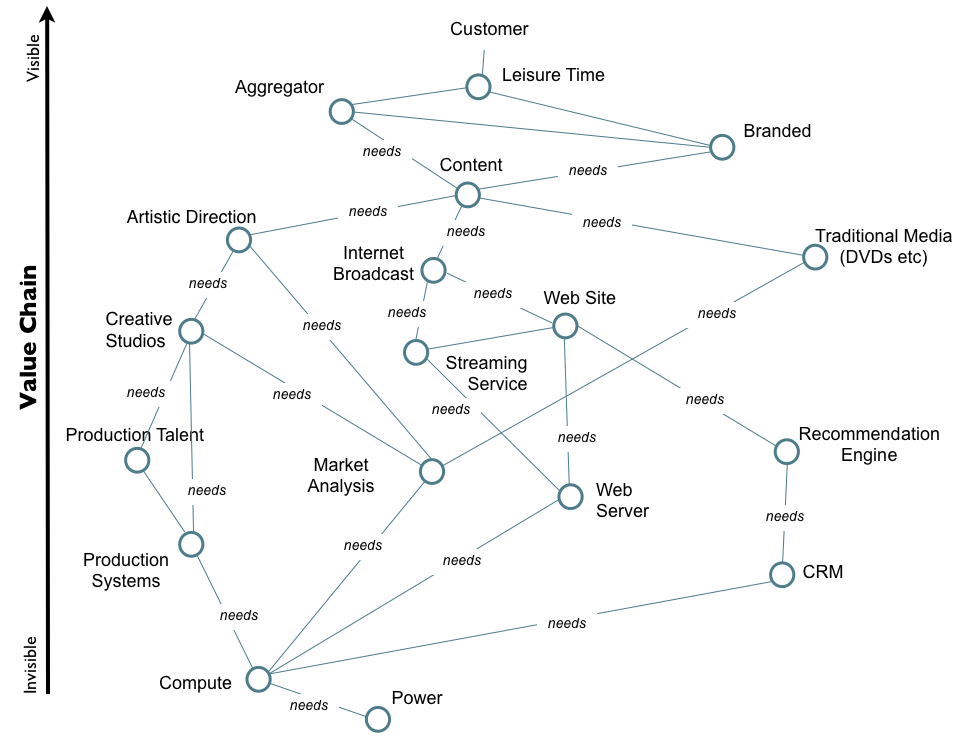

Visibility and the value chain

I’ve been thinking about visibility in the context of whole value chain maps. In his mapping technique, Simon Wardley arranges components from the most visible user needs at the top to the unseen at the bottom:

In this interpretation, visibility is said to recede as we traverse the network – the more “hops” away from the customer, the less it needs to concern them. But is that really true?

Invisible things can have very visible effects. Amazon’s recommendation engine is deeply buried in the company’s infrastructure, yet customers experience its insights and biases every time they use the site.

Visible things may get up to all sorts of unseen activities. What if that camera or video recorder in the corner is participating in a distributed denial of service attack right now?

Invisibility and commodification

Why is it that some things naturally seem to merit visibility while others have to hide themselves from view?

I think it has to do with commodification. To turn something into a commodity is to take it out of its context, to make it fungible so that it can be substituted, traded and transferred. In an example by the philosopher Andrew Feenberg:

a tree is cut down and stripped of its branches and bark to be cut into lumber. All its connections to other elements of nature except those relevant to its place in construction are eliminated.

This is what people are doing when they commit metaphorical sleights of hand such as “data is the new oil“. They take something that has deep meaning to an individual and, by aggregation, transform it into something that can be traded without further challenge or debate.

The logic of commodification prohibits the end user from interest in, or influence over, anything but the surface-level components. Before we know it, any breach of the line of visibility feels illegitimate. From Fairtrade foodstuffs to the employment rights of Uber drivers, demands to deepen visibility into the supply chain come to be seen as “political” incursions in the supposedly rational domains of technological production and economics.

Consider the much-maligned EU cookie directive.

Unregulated, the behemoths of the attention economy would place all their tracking of users below the line of visibility. “Users don’t need to know about that stuff,” they’d say. “It’s technical detail. Nothing to worry about. Move along now.” The Jobsterbedunners might even hold up web users’ continued browsing of sites in such compromised circumstances as some kind of “revealed preference” for covert tracking.

But people who care about privacy have a different opinion on where the line should be drawn. Their only option is a “political” intervention to drag the publicity-shy cookie blinking over the line of visibility. Now Europe’s internautes can take back control, every time they visit a website. Say what you like about the implementation, but we Brits will miss those privacy protections when they’re gone.

Shared light

What if there was another way to realise value? One that didn’t depend on enclosing the value chain by making it opaque to end users?

To Feenberg, decontextualisation is “primary instrumentalisation” the first part of a two-step process:

The primary instrumentalisation initiates the process of world making by de-worlding its objects in order to reveal affordances. It tears them out of their original contexts and exposes them to analysis and manipulation while positioning the technical subject for distanced control…

But the story doesn’t end there. There’s a crucial, secondary step where visibility has to be re-established:

At the secondary level, technical objects are integrated with each other as the basis of a way of life. The primary level simplifies objects for incorporation into a device, while the secondary level integrates the simplified objects to a social environment.

Through this secondary instrumentalisation, this resource integration, users tell us what they want technology to be. Think, for example, of the camera-phone as a concept worn smooth by countless buying and use decision over the course of a decade. This part of the value creation process cannot happen in strategy and planning; it can only happen in use.

Premature commodification would close down such possibilities just when we ought to be keeping our options open. Co-creation, on the other hand, places the service user, the service designer, and the service provider on the same side – and all of us play in all those positions at one time or another.

We maximise value when the interests of all the actors are aligned, when asymmetries of knowledge between them are reduced. To borrow another controversial theatrical analogy, co-creation flourishes in “shared light” when actors and audiences can see each other equally.

- Not only do we see the coffee being made, we see the staff being trained.

- We are no longer passive recipients of the recommendation algorithm, we can understand why and how it behaves.

Some service design patterns

Here are just some of the patterns that play with the line of visibility. By making things visible, they make things better.

Seeing over the next hill: We meet much of the most valuable service when facing a change or challenge for the first time. But unless we know what to expect, it’s hard for us to make decisions in our best interests, or to trust others seeking to support us. Deliver service so that people can always see over the next hill, so they know what to expect, what good looks like, and who they can trust to help them along the journey.

Provenance: People can take reflective pride in where their things come from – and be repulsed by a supply chain’s dirty secrets. Design like they’re watching. Document the journey and make it part of the service. My Fairphone may have been a little pricier than an equivalent smartphone, but it comes with a story of fair materials, good working conditions, reuse and recycling.

Individualisation: Service is intrinsically full of variation. When we treat its delivery like factory mass production, we make it inflexible, unresponsive, and ultimately destructive of value. Anticipate variation, embrace it and celebrate it. This will likely means fewer targets and processes, more self-organising, empowered teams. Be like homecare organisation Buurtzorg, which prioritises “humanity over bureaucracy” and “maximises patients’ independence through training in self-care and creation of networks of neighbourhood resources.”

A last word from actor-network theorist Michel Callon in his afterword to Feenberg’s ‘Between Reason and Experience’:

“Keeping the future open by refraining from making irrevocable decisions that one could eventually regret, requires vigilance, reflection, and sagacity at all times. Politics, as the art of preserving the possibility of choices and debate on those choices, is therefore at the heart of technological dynamics.”