“Evolution. What’s it like? So one day you’re a single-celled amoeba and then, whoosh! A fish, a frog, a lizard, a monkey, and, before you know it, an actress.

[On-screen caption: “Service limitations apply. See three.co.uk”]

I mean, look at phones. One, you had your wires. Two, mobile phones. And three, Three video mobile.

Now I can see who I’m talking to. I can now be where I want, when I want, even when I’m not. I can laugh, I can cry, I can look at life in a completely different way.

I don’t want to be a frog again. Do you?”

— Anna Friel, 3 UK launch advert, 2003

Today, in 2016, that ad feels so right, and yet so wrong. Of course phones have changed massively in the intervening decade-and-a-bit — just not how the telecoms marketeers of the early Noughties fantasised. In this post I want to trace what evolution of technology might really be like. I’ll do it by following the unstable twists and turns around one small element of the construct we now call a smartphone.

Something was missing from the Anna Friel commercial. All the way through, the director was at pains to avoid even the tiniest glimpse of something the audience was eager to see. You know, a phone. At the time I worked for Three’s competitor Orange whose brand rules also forbade the appearance of devices in marketing. The coyness was partly aesthetic: mobiles in those days were pig-ugly. Moreover, the operators had just paid £4 billion each for the right to run 3G networks in the UK. They wanted consumers to think of the phone as a means to an end, a mere conduit for telecommunications service, delivered over licensed spectrum.

To see a device in all its glory, we must turn to the manufacturer’s literature. Observe the product manual of the NEC e606, one of three models offered by Three at its launch on 3 March 2003:

Notice where a little starburst has been Photoshopped onto the otherwise strictly functional product shot? That’s the only tangible hint of the phone’s central feature, the thing that makes it worth buying despite being pricier and weightier than all the other matte grey clamshells on the market. By this point, loads of phones have digital cameras built in, but they are always on the back, facing away so the holder can use the tiny colour screen as a viewfinder. This is something different: a front-facing camera. It exists so that Anna Friel can be seen by the person she is talking to.

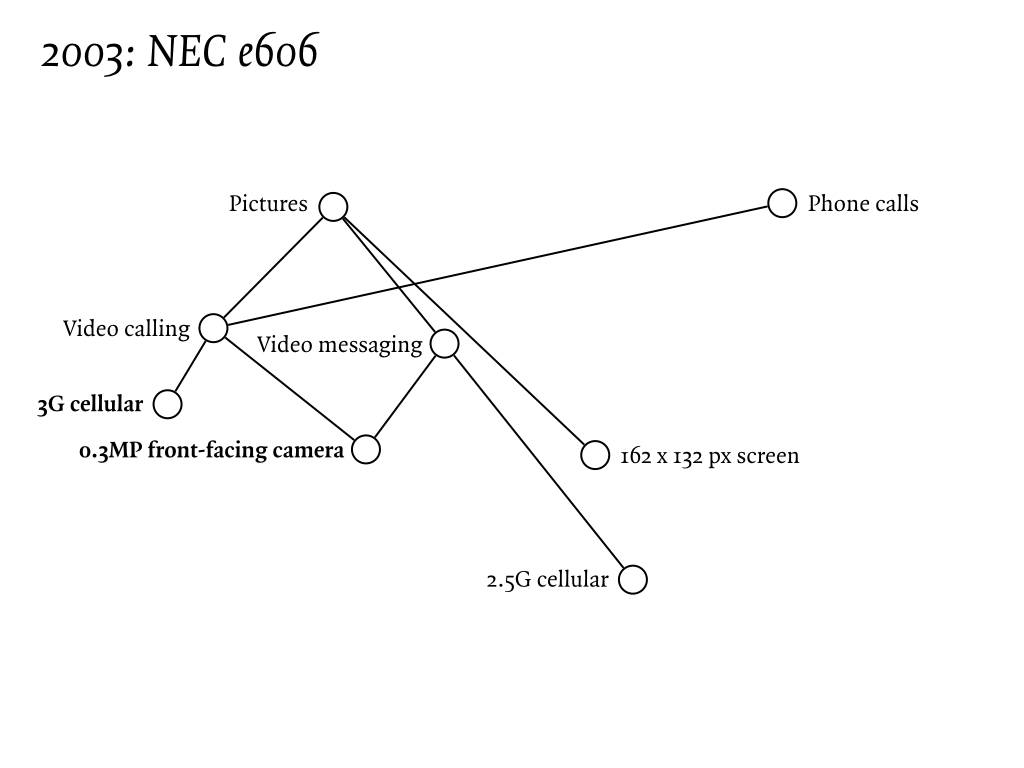

Let’s map* this network.

Loosely, the vertical axis answers the question “how much do users care about this thing?” The nearer the top, the more salient the concept. The horizontal concerns stability of the concept – the further to the right, the less controversial. But at this point the choice of nodes and the connections between them matters more to me than their precise placement. This forms an actor-network – a set of concepts that belong together, in at least one contested interpretation.

- Phone calls are over on the top right, a very stable concept. Users understand what phone calls are for, know how to access them, and accept that they cost money.

- If the operators can persuade users to add pictures, to see who they’re talking to, they have a reason to sell not just plain old telephony service but 3G, that thing they’ve just committed billions of pounds to building. Cue the front-facing camera.

- Video calling and 3G cellular networks rely on each other, but both are challenged. Do users really need them? Will they work reliably enough to be a main selling point for the device? Whisper it softly, “service limitations apply”.

- Because of this weakness, the assemblage is bolstered by a less glamorous but more stable concept – asynchronous video messaging. This at least can be delivered by the more reliable and widespread 2.5G cellular. Users don’t care much about this, but it’s an important distinction to our network.

What then remains for the telco executive of 2003 to do? Maybe just wait for the technology to “evolve”?

- More 3G base stations will be built and the bandwidth will increase

- Cameras and screens will improve in resolution

- People will take to the idea of seeing who they’re talking to, if not on every call, then at least on ones that really matter.

All these things have come to pass. But could I draw the same network 10 years later with everything just a bit further over to the right? No, because networks come apart.

Nokia’s first 3G phone, the 6630 had no front-facing camera. Operators used their market muscle and subsidies to push phones capable of video calling. Yet many of the hit devices of the next few years didn’t bother with them. The first two versions of the Apple iPhone likewise. Even the iPhone 3G was missing a front facing camera. Finally in 2010, the operators had to swallow their pride and market an iPhone 4 with Apple’s exclusive Facetime video calling service that ran only over unlicensed spectrum wifi.

This is the social construction of technology in action. Maybe evolution is a helpful metaphor, maybe not. Whatever we call it, this is the story of how, over the course of a decade, by their choices what to buy and what to do, users taught the technology sector what phones were for. Hint: it wasn’t video calling.

Just when we think the front-facing camera is out of the frame, it makes a surprising comeback. This time it’s not shackled to either video calls or mobile messaging. Instead it emerges as a tool of self-presentation in social media.

“Are you sick of reading about selfies?” asks an article in The Atlantic, announcing that selfies are now boring and thus finally interesting. “Are you tired of hearing about how those pictures you took of yourself on vacation last month are evidence of narcissism, but also maybe of empowerment, but also probably of the click-by-click erosion of Culture at Large?” Indeed, for all its usage, the term — and more so the practice(s) — remain fundamentally ambiguous, fraught, and caught in a stubborn and morally loaded hype cycle.”

— ‘What Does the Selfie Say? Investigating a Global Phenomenon’, Theresa M. Selft and Nancy K. Baym

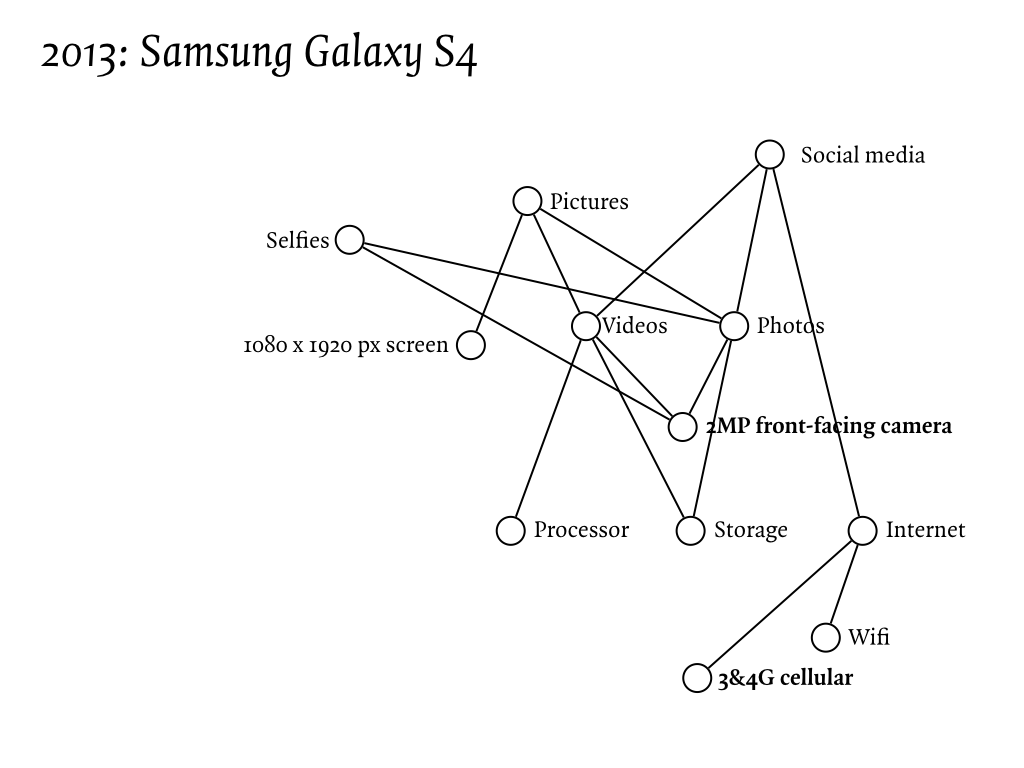

Time for another map.

- By 2013, 3G (now also 4G) cellular mobile is no longer in doubt, but its salience to users is diminished. It is a bearer of last resort when wifi is not an option for accessing the Internet.

- The lynchpin at the top right is not the phone call but social media, with its appetite for videos and photos. In their service, we find the front-facing camera, now though rarely used for calling.

- Only a fraction of selfies even leave the phone. Many of them are shared in person, in the moment, on the bright, HD screen. They are accumulated and enhanced with storage and processing powers that barely figured on the phones of 2003.

Call it evolution if you like, this total dissolution and reassembly of concepts.

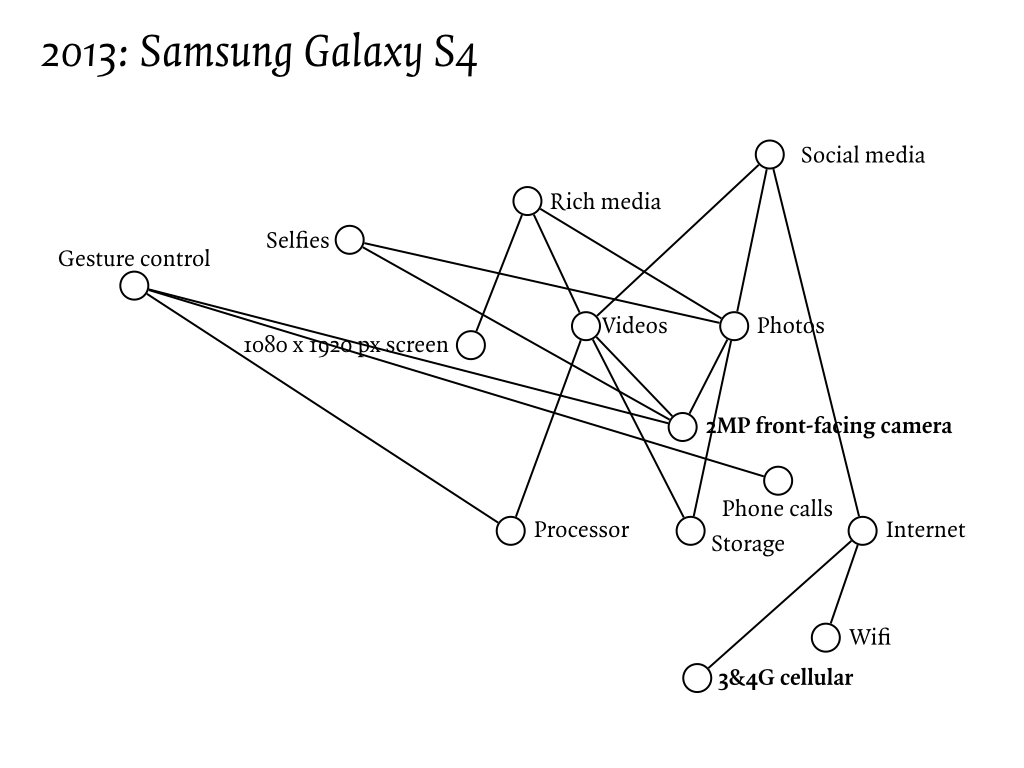

We’re not done yet. Here’s another commercial for your consideration. One for the Samsung Galaxy S4 mapped above. Can you spot the third incarnation of the front-facing camera?

Man 1: “Hey, sorry I was just checking out your phone. That’s the Galaxy S4, right?”

Man 2: “Yeah, I just got it.”

Woman: “Did your video just pause on its own?”

Man 2: “Yeah it does it every time you look away from the screen.”

Man 1: “And that’s a big screen too.”

Man 2: “Yeah, HD.”

Man 3: “Is that the phone you answer by waving your hand over it?”

Man 2: “Yeah.”

Man 1: [waves hand over Man 2’s phone] “Am I doing it right?”

Man 2: “Someone has to call you first…”

— Samsung Galaxy S4 TV advert, 2013

See how far a once-secure concept has fallen? The guy needs reminding (in jest at least) how phone calls work! Compared to the 3G launch video, this scene is more quotidian; the phone itself is present as an actor.

And what is the front-facing camera up to now? Playing stooge in the S4’s new party trick: the one where the processor decides for itself when to pause videos and answer calls. If the user never makes another video call or takes another selfie, it’ll still be there as the enabler of gesture control. Better add that to my map:

We used to think the phone had a front-facing camera so we could see each other. Then it became a mirror in which we could see ourselves. Now, it turns out, our phones will use it so they can observe us.

Maybe that’s what evolution is like.

* These maps are not Wardley value chain maps though I see much value in that technique. More on that in a later post.