In my most recent weeknote, I promised a blog post…

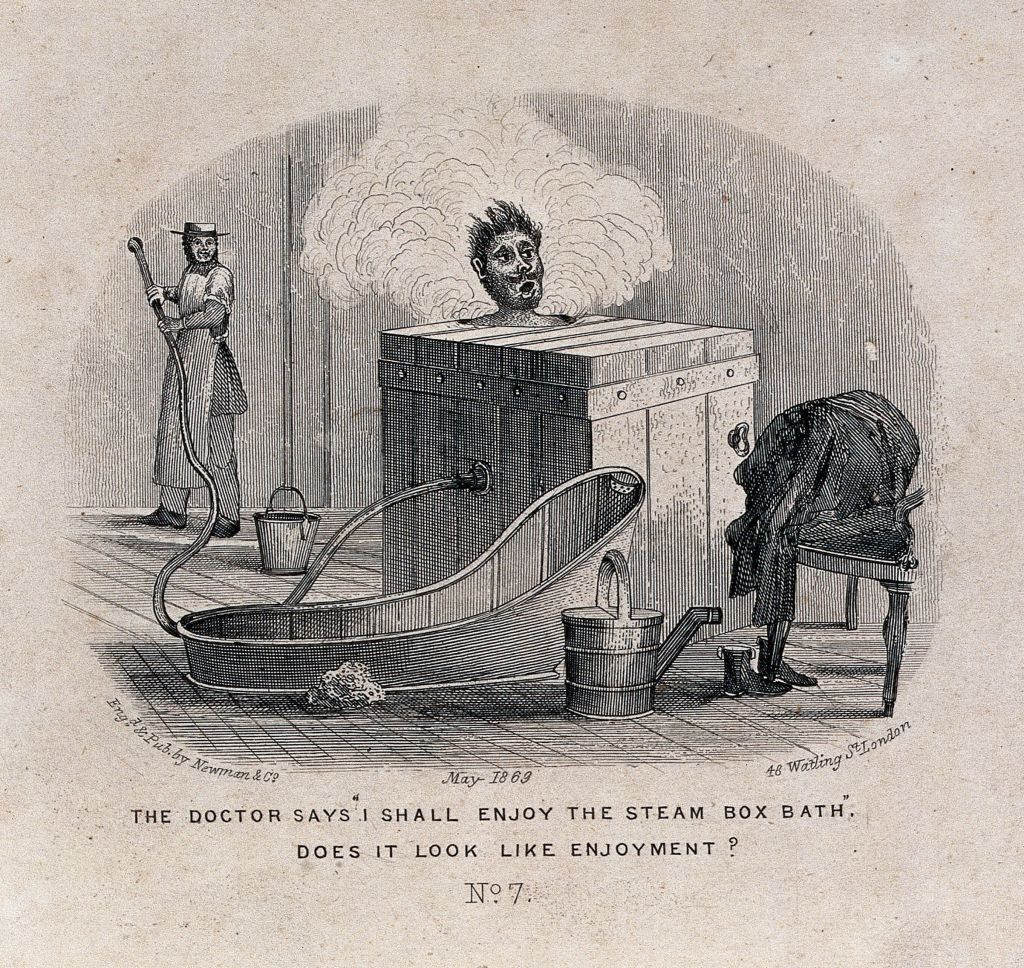

Somewhere in all this between the tepid bath of short termist repeating the things we’ve always done, and the ceiling we can’t see for the cloud of vapourware in which unproven AI and imaginary enterprise architectures magically solve all our problems – there’s a space of pragmatic ambition.

In that near future, we re-combine the assets we already have, and the ones that are emerging as we speak, to co-design a radically different patient and staff experience.

That’s where I am desperate to be working right now, and where I know my team has much to contribute.

The bait, switch, and twist

It goes like this.

- First the bait: an invitation to contribute to a multi-year strategy or plan. The service team marshal their best ideas. From their experience of performing live service at scale, they know these things would really shift the dial if stuck at for a sustained period. They have a set of initiatives, from the quick and easy to the higher value and more challenging to implement.

- But then the switch: at short notice “the ask,” anonymously from on high, has changed. Could they ditch the hard but high impact things and only include items proven to make a difference in a single financial year? With this new constraint, the team is suddenly recast as the Department of No, damned if they overcommit, damned if they underwhelm.

- And finally the twist: the plan is by now thoroughly pedestrian. When it goes to a higher echelon of decision-makers, they look on it and despair. Where’s the ambition? We don’t have long to fix it now. Could you just add something about AI? Here’s a mock-up I made in PowerPoint. How hard can it be?

I don’t blame the people involved for the behaviours that create this whiplash. We find it everywhere in our public conversation. The present-day woes of public service are easy to portray on the evening news. Meanwhile our online feeds are full of artfully staged demos involving humanoid robots and ethereally-voiced assistants. Unfortunately the messy work of innovation in between those polar opposites does not make for such compelling content.

The resulting chasm between current reality and future vision severs short term from long term planning. It leads to an incoherence of problem framing and policy interventions, in which decision-makers have to make vague vibes-based guesses about the timeframes across which change might actually be achieved. Real opportunities are missed while chasing imagined futures.

Don’t get me wrong. The future can be better than the past. AI and machine learning will transform our everyday lives. But only if we do the hard work to make them useful. The very idea of artificial intelligence is a social construction: as much an experiment of humans upon ourselves as a test of the powers of computer science.

Bridging the gap

The good news? It doesn’t have to be like this. We actually have tools for thinking about transformation in a structured way. Through my career they’ve helped me to innovate out of a rut, and to add nuance to wrong-headed false oppositions such as “bimodal IT” and “build or buy” (in digital, every builder is also a buyer, and every buyer ends up a builder whether they mean to or not.)

To name just a few of my favourite models:

The cone of uncertainty is a useful thought experiment to bridge from the here and now to a range of better futures. Short term gains can be necessary, but if a team is only ever asked for quick fixes, the range of options offered up will always be uninspiring. At the other extreme, trying to cast the net a decade hence carries so much contingency that the result will inevitably be indistinguishable from science fiction. In the middle of the cone is a sweet spot both credible and rich in policy optionality.

Stewart Brand’s pace layers remind us that fashion and commerce move fast, while culture, governance and nature take longer to shift, but with greater impact when they do. How might we build a balanced portfolio of interventions that will bear fruit in different timeframes? This means responding rapidly to the public’s rising expectations, as shaped by their fashion-driven use of social media and digital services. Yet at the same time, we should be patiently investing in the infrastructure and institutions that may take more than a single political cycle to embed and become productive – the things that will make it easier for us to respond at pace to the next pivot even if we don’t know what or when it will be.

Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework helps us make sense of complexity. How do we spot when the simple rules that used to work for us no longer apply? When the time has come to strip away the complicated layers because something has changed in the world? At first it seems as if the situation is chaotic, we do something, anything and see what happens. We reach for the levers we can control. Cut this, abolish that. Then we learn the humility to keep working together in true complexity using imperfect data to drive our next steps, “probe–sense–respond”.

Simon Wardley’s Pioneer, Settler and Town Planner model identifies three attitudinal segments among technologists, each of which has a different set of assumptions and tools. As Simon emphasises, all three groups contain wonderful people:

- “Pioneers” create ‘crazy’ ideas, but half the time the thing doesn’t work properly.

- “Settlers… can turn the half baked thing into something useful for a larger audience. They build trust. They build understanding. They learn and refine the concept.”

- And finally “town planners” turn products into platforms. They find ways to make things faster, better, smaller, more efficient, more economic and good enough.

I’m a proud to be a “settler”, but I know the value of my pioneer and town planner friends and colleagues. I am also alive to the perils of creating handoffs between the three groups instead of encouraging them to collaborate in multidisciplinary teams of teams.

Pragmatic ambition

All the above are tools for practicing pragmatic ambition, which is at once the most realistic and the most radical position to hold. Without them the discourse around technology is destined to thrash aimlessly between fearful nostalgia and starry-eyed wonder.

To borrow a controversial metaphor and stretch it to absurdity, this is not the tepid bath, where we are content to keep doing the same things we’ve always done in the hope that something will turn up. But neither is it vapourware, asserting that technology will solve our problems in some unspecified future always just around the corner.

Pragmatic ambition is asset-based, rooted in the real world. It starts with capabilities that we and our users have right now. Because we are part of a socio-technical system, these assets take the form of both technological and human capital: the amazing capability of today’s modern smartphones, and the alacrity with which unexpected sections of society have adopted them. What matters is how we combine these assets, enabling people to do more with technology, and technology to better fit into the aspects of life where it is deployed.

Pragmatic ambition allows us to be attentive and imaginative, to notice what new assets are emerging and pull them into useful solutions. How are people solving this problem for themselves in the absence of a functioning service? What looks like a toy today, but might be a professional tool tomorrow?

Rather than trying to divine the best possible future architecture from first principles, we embrace path dependency. Past events and decisions constrain but never totally predetermine what happens next. We amplify the good while dampening the bad.

To adapt a set of questions from Asset Based Community Development:

- What might be enhanced?

- What should be restored?

- What must be replaced?

- What might this mutate into?

Radical reconfiguration

Using these tools and attitudes, we can embark on a radical reconfiguration of our services – one that is credible and achievable in ways that the magic bullet solutions are not.

We must following users’ whole journeys, and understand the potential roles that various new technologies could have depending on how they are situated in the work as it is really done. This enables us to pinpoint and squeeze out failure waste – all the activity that the business continues to perform which on close inspection adds no additional value. Given what we learn from user research with all the actors involved, might there be a better, less burdensome way of meeting their needs? Before trying to make a process more efficient, we ought to question whether it needs to exist at all.

I have learned that this work is best done as co-creation, with and by all the actors involved in the service, staff and service users alike. It does require a trusted space. On a couple of occasions in my career I have had to withdraw co-creation approaches from organisations where staff or public trust was so tattered that honest and productive conversation proved impossible.

I have also concluded that co-creation is a practice best done in a place. Co-creation reaches another level when translated to a local context in a real community. While we in national organisations can and should bring users into our work, we gain greatly by also connecting with the places where we’re based (hello Leeds!) and show humility in the face of things that locally-embedded teams know which central ones will never see. The partnership of national platform and hyper-local adaptation could be immensely powerful. See also ‘Test, Learn and Grow’.

This fragile space

The conditions for successful innovation are hard won and easily thrown away. There are leadership behaviours that create the space for this work, and behaviours that shut it down, even inadvertently.

But when we get this right, the payoff is huge. Between the tepid bath and the cloud of vapour – that’s where innovation really happens.

2 thoughts on “Between the tepid bath and the cloud of vapour: a plea for pragmatic ambition”