In 2015, Tom Loosemore asked if anyone had written a blog post about how “most of government is mostly service design most of the time”. I couldn’t find one, so I wrote it myself. Thanks in large part to a link from the awesome UK government design principles, that post has been viewed more than 12,000 times, making it easily the most popular entry on my blog.*

Now I work in design for health and care, and I see the same patterns playing out.

People in this sector talk a lot about “service redesign”. I find that odd because, on the available evidence, much of the service we have today was never consciously designed. It emerged through countless policy decisions and reorganisations. Someone responsible for part of the service made changes that seemed like improvements in isolation, but often had unintended consequences elsewhere. Every time we make another tweak, we risk making matters worse – unless we step back and consider the system.

The system nobody sees

My go-to model for this system comes from the world of service marketing. The Gaps Model of Service Quality (Parasuraman et al., 1985) seeks to explain how a chasm so easily opens up between what users want, and the service as they perceived it.

The model shows how five specific kinds of gap can arise in complex service:

- between what users expect and what managers think they expect

- between understanding of expectations and service as designed

- between design and delivery

- between promise to users and what’s actually delivered

- between what users expect of service and how they actually perceive it.

Take all the dynamics above, and put them together for a system-level view that looks like this…

Gaps can be both intellectual and emotional. Cumulatively, they explain how empathetic people end up delivering unempathetic service. The individuals are lovely. But they’re trapped in a system that prevents them from understanding, designing for, or delivering to meet, user needs.

Halfway down the diagram, is a dotted line, the “line of visibility,” a reminder that users shouldn’t be expected to become experts in how the service organisation works, nor can the organisation ever be expert in people’s lives. New value can only be created when both work together.

Wherever there’s a gap, there’s failure waste. That’s the extra cost incurred through not meeting user needs comprehensively, first time around. Inability to see across the line of visibility means failure waste is often understated in cost models and financial reports. This in turn may lead to the complacent belief that our service is already well designed.

Here’s what we have to do.

1. Start from the patient’s point of view

Many things shape people’s expectations of service:

- communications from the service itself

- what they hear in the news

- word-of-mouth from friends and family

- their own past experiences of the service

- their experiences of other, increasingly digital, service

People experience service as one from beginning to end, not in the organisational silos that deliver different parts of it. We need to research their experiences and design holistically. For example, the experience of an outpatient appointment begins with referral and booking, and includes travel and parking, as much as what happens in the consulting room.

Perceptions of service always exist in the context of the user’s everyday life. People are the experts in their own lives, so where possible we should design service that puts them in control. Only the patient knows whether she would prefer an early appointment so she can get on with her day, or a later slot that makes off-peak travel a possibility.

Because most of the context is their life not our service, asking users for feedback on the service alone is not enough. If we frame our inquiry as just about the service, users won’t think to mention many of the things that are relevant to their experience. And with a subject as important to them as health care, people can also be reluctant to tell us what they’re really thinking, in case this causes trouble for themselves or for others.

Service should serve the whole person, and mirror what’s important to them in the moment. To a person who is ill or under stress, little details matter greatly.

2. Support the people who serve

The people who deliver service need to understand the end-to-end experience, not just the part that they deliver. If they don’t, even with the best of intentions, they can make things worse for the people they’re helping. Perhaps they miss an important piece of information, or make an assumption about the patient that turns out to be wrong.

It’s right that they have a lot of discretion to meet the needs of their users. But to use this discretion effectively, they need flexible systems that surface what’s important to each person – not only the clinical information, but also the person’s preferences, their support network, their hopes and fears.

And if a service doesn’t work well for staff, they’re unlikely to recommend it to their users. Why would a receptionist recommend appointment booking by app to a vulnerable patient when the computers she has to use for work cause her nothing but frustration?

3. Recognise that to manage is to design

At the root of the problem, user needs and expectations are often misunderstood by decision-makers. That’s no wonder, because user feedback is often confusing and contradictory.

When we consult in general terms, we tend to get general answers, or responses to issues that don’t seem relevant to the task in hand. A service manager might go to a public meeting to consult about changes, and hear nothing but complaints about parking. It takes skill to dig beneath the surface and see what really matters to everyone who uses the service.

When we rely on proxies for actual users, or fail to hear voices that reflect our users’ full diversity, we miss important pieces of the user needs jigsaw.

Even when needs and expectations are understood, it takes specialist skills to translate them into successful service design. We need to apply some different capabilities, not haphazardly, but at the right points in design and delivery.

4. Nurture new capabilities

User research, so often approached superficially, is in fact a deep specialism. To form a good picture of users’ needs and expectations, user researchers combine insights from multiple sources, qualitative and quantitative. They interpret the research evidence carefully, and use it to bring user needs to life, ideally in jargon-free language that users would use themselves.

User research can be both a dedicated role and a team sport. There’s good evidence that everyone on the team should spend at least 2 hours every 6 weeks observing primary, qualitative research. This is just enough to keep empathy levels topped up. We must to avoid the pitfalls of untested assumptions and self-referential design.

Likewise, service design, by which, along with Lou Downe, I mean simply “the design of services”, is also a specialist skillset. That’s not to say that only professional service designers can do it. Design thinking and service design techniques should be democratised and adopted by the widest possible range of people. Service at scale is a complex thing that demands multi-disciplinary skills and perspectives, but there are service design craft skills that take time to learn, especially for people already steeped in a professional paradigm other than design.

Service designers work collaboratively and iteratively to:

- visualise complex processes to make them more comprehensible

- use data to interrogate the problem, and the context in which it exists

- facilitate co-design with users and the people who deliver the service

- make prototypes to test lots of possible solutions

- orchestrate service across multiple online and offline channels

- pace the service across multiple encounters, using time as a material

- chip away until they fully understand the shape of the service.

There are other specialised design skills too:

- If you find yourself making an interactive form or tool, you need an interaction designer.

- Structuring information? An information architect.

- A dashboard? A graphic, or information, designer.

- Words and pictures? A content designer.

- Need a service that works for everyone? (Hint: of course you do!) You need designers and developers with inclusion and accessibility expertise.

5. Design the design process

What all good designers of any stripe share is a user-centred design process. There are design principles, and even an ISO standard for that.

User-centred design pairs well with the modern agile practices that are increasingly the norm in other parts of public service. This means a move away from Big Design Up Front (BDUF for you acronym lovers) to an iterative process where user researchers and designers are embedded in self-organising, multi-disciplinary teams. Just as medicine thrives on experimentation, so user-centred designers relish alpha and beta versions and repeated rounds of multivariate testing to refine their designs.

Where should the service designers sit in the organisation? The gaps model shows a specific disconnect between communications and service delivery – because often these things are silos too. As organisations, what we say doesn’t always translate into what we do. That’s why service design can never sit wholly in “communications” or in “operations”, but as a coordinating function that orchestrates them both.

6. Be here for the long term

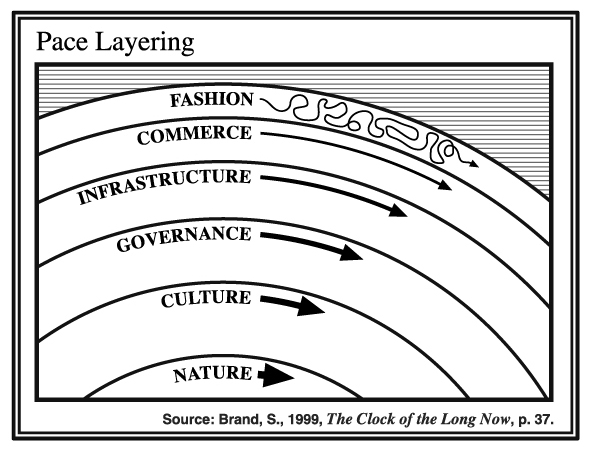

Service design treats time as a material. In my original “mostly service design post,” I alluded to Stewart Brand’s concept of “pace layering”:

The six Pace Layer levels in descending order from the highest & fastest to the lowest & slowest are Fashion, Commerce, Infrastructure, Governance, Culture, Nature. – Stewart Brand, Paul Saffo, ‘Pace Layers Thinking’

Planning for the long term means infusing service design thinking deep into the governance and culture of our organisations, not just in the latest shiny user interfaces.

Fortunately, the NHS has a Long Term Plan, and it contains references to many individual services, each of which would benefit from service design (not just service redesign):

- access maternity notes

- record information about your child

- transition to adult services

- use wearable devices

- work out what to do next

- get an appointment

- be prescribed medicine

- be referred to specialist services

- use rostering and job planning

- get decision support

- link clinical, genomic and other data

- hire specialist staff

- aggregate procurement demand

- process invoice payments

But above that are some over-riding principles, which also look like design problems to me:

- more joined-up and coordinated care

- more proactive provision of services

- more differentiated support of individuals

To develop a new service model for the 21st century, we need to recognise more of the decisions we make for what they are – service design decisions – and skill up our organisations accordingly.