I’m typing this on the sofa. Across the living room, the laptop display is mirrored to the television. I can comfortably read them both. Unremarkable to you, maybe. To me it seems like magic because just before Christmas I picked up my first pair of varifocals.

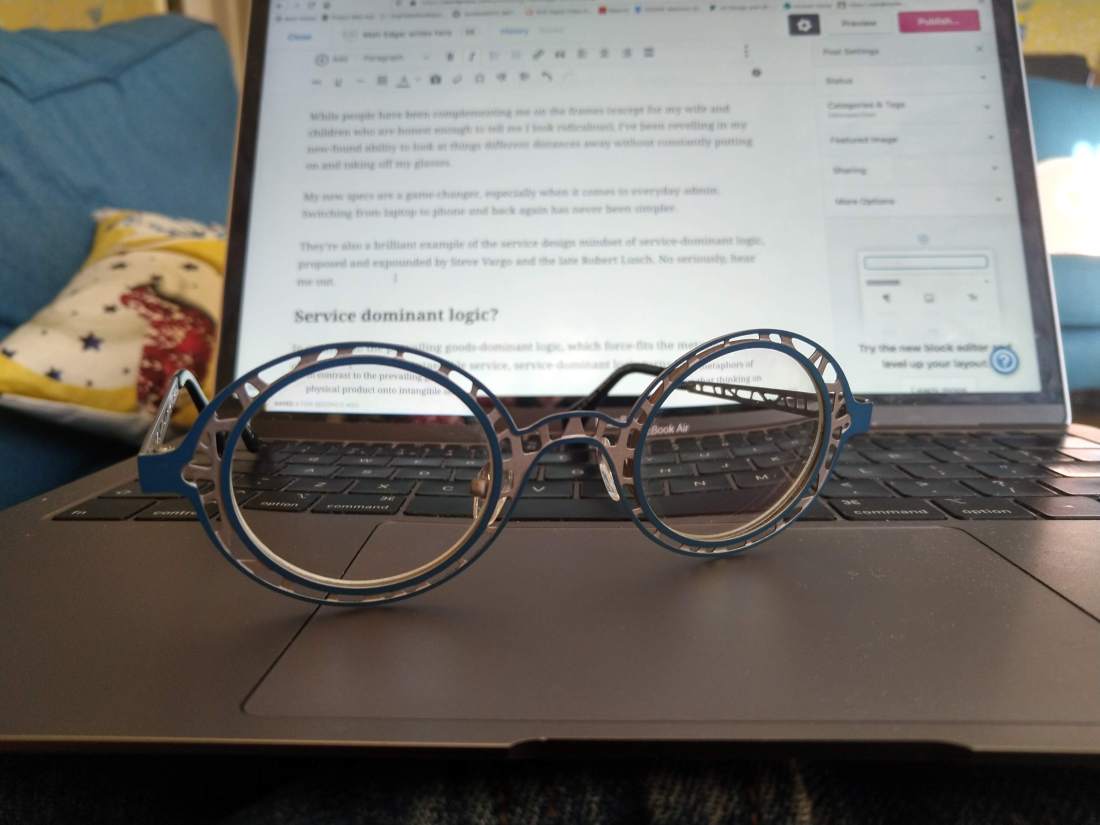

While people have been complimenting me on the frames (except for my wife and children who are honest enough to tell me I look ridiculous) I’ve been revelling in my new-found ability to look at things different distances away without constantly putting on and taking off my glasses.

My new specs are a game-changer, especially when it comes to everyday admin. Switching from laptop to phone and back again has never been simpler.

They’re also a brilliant example of the service design mindset of service-dominant logic, proposed and expounded by Steve Vargo and the late Robert Lusch. No seriously, hear me out.

Service-dominant logic?

In contrast to the prevailing goods-dominant logic, which force-fits the metaphors of physical product onto intangible service, service-dominant logic turns that thinking on its head:

“The foundational proposition of S-D logic is that organizations, markets, and society are fundamentally concerned with exchange of service—the applications of competences (knowledge and skills) for the benefit of a party. That is, service is exchanged for service; all firms are service firms; all markets are centered on the exchange of service, and all economies and societies are service based.”

Vargo and Lusch summarised this thinking in 5 axioms.

- Service is the fundamental basis of exchange.

- Value is cocreated by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary.

- All social and economic actors are resource integrators.

- Value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary.

- Value cocreation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements.

As I got used to moving my eyes instead of peering over my specs, I realised that optometry makes a brilliant case study of how these axioms apply in the real world.

Service is the fundamental basis of exchange.

In the words of Richard Scarry’s seminal treatise on microeconomics, ‘What Do People Do All Day?’ everyone is a worker.

My work with screens means that every couple of years, I can get a voucher from my employer to pay for an eye test. I give the voucher to the optician who, judging by his bronzed complexion and our biennial conversations, uses the money he gets to indulge his love of cruise ships.

I provide my services, the optician provides his, and so do the sailors. The vouchers and money only mask what’s really happening here: it’s service all the way down.

Value is cocreated by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary.

It took the accumulated actions of numerous people to make my new glasses worth hundreds of pounds:

- Somebody worked out where to dig, somebody had the physical skills to prise the raw materials out of the ground, though I’m sure I didn’t pay that much for mere metal and sand.

- The designer of the frame used knowledge of fashion trends, material properties, and human heads to create something that would catch my eye and fit over my ears.

- Manufacturer and distributor ensured that the frames would find their way to a rack in a north Leeds optician’s shop.

- My optician used his training and years of experience to test my eyes, measure the distance between them, and design bespoke lenses to meet my needs as an office worker.

- Someone ground the lenses to a precise specification and coated them to prevent glare.

- Someone set the lenses into the frames and packed them neatly into a glasses case with little cloth for cleaning.

Even then, someone was missing: me, the beneficiary.

- I had to be there, as an active participant, in the eye test. I answered question after question: “Can you read the second line from the end?” “Does the red look sharper or the green?” “What if we add this lens?” If I missed my appointment, the optometrist’s time would be wasted.

- And only when I put the specs on for the first time, allowing light to flood through the lenses and into my uniquely defective eyes was the value in all this work finally made real. Without me to wear them, the glasses are worthless.

All social and economic actors are resource integrators.

At every step we combined tangible and intangible resources to get this result:

- The designers and manufacturers worked at the intersection of ergonomics, material science and fashion.

- The skills of the high street optician combined the medical, mechanical and retail.

- My choices as the customer led to this particular combination of lens and frame.

The resource integration didn’t end there, because my new glasses now influence how I configure the font sizes and settings on my phone and laptop, and how far away I hold newspapers and books when I read them. The glasses are now part of a sociotechnical system that augments my human capabilities.

Value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary.

What do my new glasses mean to me?

The lenses bring me freedom from faff, fewer fingerprints from constant doffing and donning, the ability to more seamlessly log in using two-factor authentication on mobile and laptop. At work I can be more present for my colleagues because I can look down at a document, then look them in the eye for a frank conversation.

My choice of frame was an emotional one.

Ever since I drew my social media avatar more than a decade ago, I have identified strongly as someone with round glasses. I felt the move to varifocals – a minor milestone of middle age – deserved a little more flourish than usual. I wanted a frame that would outwardly represent this invisible triumph of optical engineering.

I try to explain this to my family.

“No one’s laughing at the lenses,” says my 13-year-old.

“Thank you,” I say, “That’s my post header right there.”

All this value is mine. Other glasses wearers will weave their own stories.

Value cocreation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements.

It’s little short of a miracle that we made all this happen, and do so day in, day out, through global supply chains, and just-in-time, bespoke manufacturing.

There’s no single right way for these institutions to work.

That the provision of eye tests should be employer funded, or that basic frames are subsidised for people on low incomes – they’re all choices of policy.

The operation of markets and trade barriers guides where to put institutional boundaries along the supply chain, whether design, manufacture and distribution should be onshore or offshore, tightly integrated or loosely coupled.

Humans made these institutions, and we have it in our collective power to change them if we need to.

Service made solid

This flimsy, fragile, preposterous artefact resting on my face embodies science, fashion, know-how, social relations and personal autonomy.

Service designers understand all that as material to be explored, worked, reconfigured and worn smooth to effect an outcome.

When we intervene in such a complex system – for example by introducing a digital service where previously there was only human interaction – we know we need to tread carefully.

A goods-dominant account would focus on the glasses as tangible object, not as embodiment of the optometrist’s intangible service. In so doing, it would miss much of the value and nuance.

Service-dominant logic gives us a mindset for understanding and working with service complexity, even when the products involved seem deceptively simple.

One thought on ““No one’s laughing at the lenses”, or the service-dominant logic of my new pair of specs”